OFF the record

What happens to your files after you leave school?

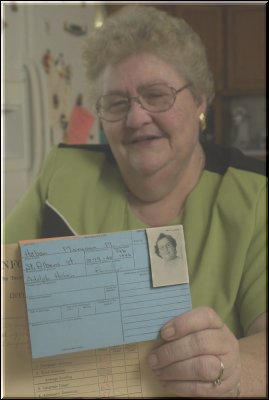

Photo by ALISON REDLICH, Burlington Free Press

(The above photo is scanned from the newspaper and does not reflect the actual of Alison's work)

PAPERS FROM THE PAST:

WHEN HIGH SCHOOLS NEED TO CLEAN HOUSE, WHAT DO THEY DO WITH DECADES OF STUDENT FILES? IF YOU'RE A STUDENT AT BFA, FAIRFAX, YOU CAN ACTUALLY GET THEM BACK

By Erica Jacobson

Free Press Staff Writer

FAIRFAX -- The material accumulated slowly in Maryann Hoben's student file during her 12 years at Bellows Free Academy in Fairfax.

A school photo was added somewhere around fifth-grade, preserving a hairstyle she would rather forget. Report cards also landed in the file, and so did the standardized tests Hoben and her classmates took.

"There were booklets put on our desk, and there was a clock running," said Hoben, now married and known as Maryann Raymond. "And I hated them."

Raymond and 15 classmates graduated in 1958, and her student file joined that of past BFA classes in the school's vault. She first thought about the file recently when she decided to claim it and save it from the shredder.

"You know, that's something I never even thought of looking at," she said, "but how neat to have and pass on to the next generations."

Vermont's high schools are required by state law to keep student transcripts -- a litany of basic student information, classes taken and grades earned -- forever. Materials such as photographs, correspondence and writing samples fall into a gray area. The information is still considered confidential, but its preservation is not mandated by the state.

Some high schools shred this extra student information after several years. Others send graduating students off with as much of their excess educational material as they can. None are required to take out newspaper ads, as BFA guidance department secretary Diane Zeno did, and attempt to reunite former students with their files.

"We have the legal right to destroy it or offer it," she said, "and I find the offering part wonderful."

Zeno has fielded at least 250 requests for files -- roughly 242 more than the last time the school offered past students their information in 2000. While she fulfilled a few of the early requests right away, Zeno now has a list of former students who have contacted her. She will research those files in the coming months during trips to the BFA vault with its double-stacked file cabinets and temperature forever a few degrees cooler than its surroundings.

"It's been wonderful," Zeno said. "The cursive writing way back when was just beautiful."

The current call was put out to students with last names from M to Z who attended the school between 1947 and 1989 as well as all students between 1990 and 1995. Although Raymond's file under "Hoben" was technically culled in past, there was some additional material left in the file that Zeno sent out.

The material that goes unclaimed will eventually be destroyed, confidentially.

"Confidentiality is the blessing and curse of schools," said Scott Lang, co-principal at BFA. "It's a trust thing. You trust us with your most intimate information, and we're not going to betray that trust."

Time and effort are the biggest obstacles for most schools when it comes to dealing with the disposal of the information.

Tom Gibson, guidance director at Essex High School, said his school has graduated as many as 300 students a year. As it is, a staff member already has to stand at a shredder and feed the material through. Coordinating a return program would require even more planning and attention for something not required by law.

During the decades that Gibson worked at Burlington High School, he packed that material into his car for the trip down to the furnaces at the now-defunct waterfront Moran electrical plant.

"I'd take them down there and watch the guy throw them in," he said.

Raymond is glad that her alma mater decided against wholesale destruction of the documents.

A fire destroyed her mother's records from the 1920s and 1930s, but she has requested, received and sent her brothers' files to their Florida homes. Her three daughters have their files, and Raymond is now working on getting the records for some of their friends.

As for her own file, Raymond tucked the file -- complete with its forgettable photo -- in with other personal information that will be passed on through the family.

"I've never heard of another school offering these things," she said. "I guess that's the unique thing about Fairfax. We were thought of before they went ahead and did their jobs.

"It's a nice way to say back to the community, 'We remember that you're there.'"

(The above photo was taken by Alison Redlich, Free Press and scanned from the local newspaper and in no way reflects the actual quality of Alison's work)

Diane Zeno, a secretary for the guidance office at Bellows Free Academy, stands in the doorway of the vault that houses most of the school's student records dating back to the mid-1940s.

|